The first time I saw a life-threatening traumatic injury, we were called to transport a motorcycle accident victim who was unrecognizable from the massive skin avulsions and broken bones where his face used to be. He had rear-ended a car on the highway, sending him head-first over the vehicle only to be stopped by the asphalt against his bare skull. I was a 19-year-old EMT going into psychological shock just at the sight of him. I remember walking out of the hospital towards the ambulance, slowly surrendering to near-syncope as I went. The ringing in my ears started to muffle out all other sounds, my vision tunneled and blurred, my breathing quickened, and I held the wall for support as I felt my way back to the rig. My thoughts raced between, “I don’t know if I can handle this – I’m going to pass out – I cannot believe what I just saw was once someone’s face – breathe – …and – If I don’t help this man, who will?” I’ve carried that motto with me every time I question myself – “If I don’t help this person, who will?” I pull through, I focus, and I get the job done (we deal with the psychological stuff after work, right?)

Working in emergency medicine in a small town is one of the hardest positions I have ever encountered in my career. Every critical 911 dispatch enlists a little prayer, “Please don’t let it be someone I know.” This is the risk we take when working in emergency response. I have heard countless stories of individuals having to treat their own family members because they happened to be the crew dispatched to the scene. One of the most horrific stories I’ve heard is of a Canadian paramedic, Jayme Erickson, who unknowingly attempted to save the life of her own daughter, Montana, after a fatal motor vehicle accident in November 2022. Montana was unrecognizable to her own mother from the amount of trauma the accident had caused. This is a healthcare worker’s worst nightmare, and yet we take on that risk and keep answering the call. But at what cost?

When I first transitioned from the field into an inpatient setting, I was heading toward my 21st birthday. It was the first year I had to wash the flesh of deceased individuals and place them into body bags for the morgue. Previously, in the field, the dead weren’t stripped naked and cleaned before being zipped up and shipped out. We simply covered our noses from the stench of decomposition and carried on with the task as quickly as possible. We could be disconnected and move on with our day because all we knew about them was where they took their last breath. (Or do we choose to tell ourselves that to avoid processing yet another traumatic memory? Did you see that picture with their children on the bedside table? Was that their favorite show still playing on the TV? When was the last time they played that guitar?) You cannot do that in the long-term care setting. There, you see these patients every day. You speak to them, hear their life stories, know their names, meet their family members, and wait for them to die. Long-term care and rehab floors are an entirely different outlook on what it means to have quality of life. I began to recognize the signs of hospice patients reaching their last hours, the empty voids in their eyes where the will to live used to be, and the acceptance that death is near and inevitable. I witnessed my first coma patient be taken off his life-support… which was in the form of a feeding tube. “It would be a few weeks at most before he would pass,” they told us, “He was too weak to survive much longer than that.” Two months later we were washing his skeleton body, talking to him as we did his daily cares, and hoping that he would go at any minute… because why?! Why should someone have to be starved to death like this? How painful that must be. How disgusting are we for wishing death upon someone…or does that make us humane?

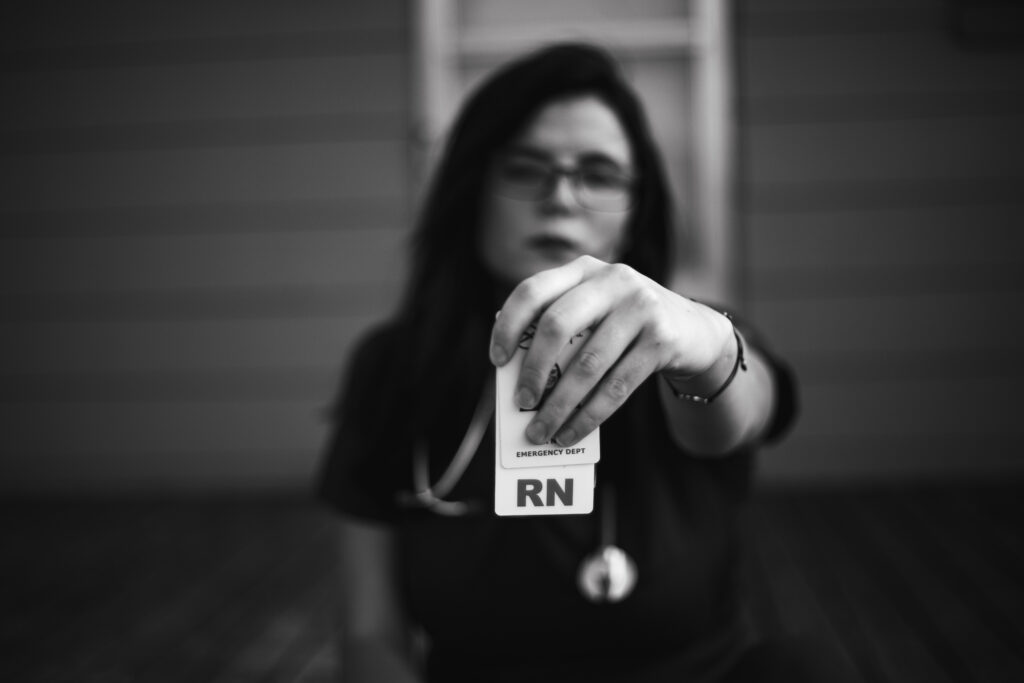

The first year as an Emergency Department RN was my most traumatic (or have I gone numb?). It was the first year I performed CPR on a child. Search crews and paramedics were scouring for him for over an hour…lost underwater somewhere in the river. A boy visiting with his church group, who moved here from across the ocean to evade a county filled with violence and threats. “His parents relocated him to keep him safe,” his church leader had told us when I stood by the ER physician as we made the unbearable announcement that the child could not be saved. My heart was breaking as we tried our best to fight the tears (there are still other patients to be seen). I remember washing the blood out of every crevice of his face to hopefully take away even a little of the traumatic impact this image was going to stain on his parents’ minds forever. I wished he could look like he was sleeping and at peace… not like he had been in this battle for his life. I wished his body wasn’t swollen purple and blue, a repercussion of the water we released from his lungs upon intubation. Our amazing physician had done everything in his power to desperately save this child, we worked as the smoothest team I’ve ever witnessed to this day, and yet… there was truly nothing we could’ve done to save him. His parents had gotten the worst phone call of their lives and were driving up to see their lifeless boy… I selfishly remember calculating what time they would arrive with gratitude that I would not be on shift to hear their mourning screams that night. I don’t think I would’ve ever been able to forget them… just as much as I will never forget the face of their dear child.

I could continue for pages explaining details of the events that plague my mind. These scenarios are snippets of the things that healthcare workers deal with daily. You can be as young as 16 years old to join a volunteer ambulance service or become a certified nurse assistant in the United States. You can be 18 to start working as a nurse or a paramedic. Now, I am not insinuating that someone at that age does not have the capabilities of being a good healthcare worker, I am stating these facts to recognize that youth witnessing such traumatic events can lay a foundation for disassociation, detachment, depression, anxiety, and PTSD when not handled appropriately. Our country has a broken system when it comes to the mental health of its citizens. People live on autopilot trying to forget what they’ve seen instead of getting the help they need. The cost of therapy drives away the pursuit of emotional healing from those who need it most. Medical professionals get shamed for expressing their distress. We are instructed to “Get back to work – It’s just part of the job – you signed up for this – brush it off – you’ll get used to it eventually.” We are all experiencing similar events and working through these struggles on our own. The few that do reach out to a coworker, hope they will let us get it off our chest without judgment. The fear of appearing weak to your peers as a new grad is not something to undermine either. How often has a new grad expressed how they were affected by their patient’s death? How often have you asked… sincerely… when there was time to talk? Do preceptors reach out to their trainees on days off to allow for some time to break down and process? Do hospitals hold debriefs or offer support? Do they provide their staff with access to mental health help after such events? What events warrant this? And what ones are “just part of the job?”

I wish I had the courage to speak up back then. I imagine how different I would’ve felt if I talked with a coworker instead of crying myself to sleep. I wish I had known that seven years later, things still get to you. I wish I had known that the senior nurses might’ve understood. I didn’t have to torture myself for wondering what I missed every time someone died. I didn’t have to think I was a terrible nurse and maybe I wasn’t strong enough for this profession. It could’ve been so different. I might’ve felt more secure with the deep conversations waiting to be had. I might’ve connected with my coworkers quicker as we bonded about the unspeakable things we’ve seen. We could’ve helped each other through it instead of feeling so alone. Maybe, we would all still be alive today.

Suicide rates among healthcare professionals are continuously increasing, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. The aging population is putting high demand on a healthcare system that does not have the staff to support it. Following this trend, is a mass exodus of nurses choosing to leave the bedside for alternative healthcare careers, or leaving healthcare altogether. (Can you blame them?) Burnout is eating them alive. Mental health MUST be a priority if we are to regain the compassion and endurance required to maintain a long-term career as a healthcare professional without losing more of the workforce to suicide.

We must care for ourselves as well as we care for others.

We must talk about it.

We must make a change.

We must take the first step.

Reach out to coworker today and ask if they’ve ever spoken about their most traumatic day. Have they tried and no one listened or were they greeted with understanding and compassion? What were they told to do to help them through that time? How can you be there for one another now?

When we clock out… who is there to listen?

References:

https://nurse.org/articles/suicide-rates-high-for-female-nurses/

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/paramedic-jayme-erickson-treats-own-daughter-deadly-crash-canada/